Pre-Production, Demystified

How does an artist build a body of work in the pre-production stage?

It’s the end of the Chinese New Year holidays and people keep asking me what I’ve been up to during my time off. My standard answer is the truth: I’ve been focused on the pre-production stage of my new album project. My non-musician friends often follow that up with questions, like:

“So, are you just writing down all the music and sending it to your musicians?” [No, no, not scoring. I might chart it later for the players, though I’m not writing down musical notes on a staff like Mozart or Beethoven! But, that’s impressive when musicians do it!]

Or, “Are you spending all this time recording your parts?” [Yes, but they are just demo parts, so when it’s all through the first stage of formal production, I’ll re-record my parts again.];

Or, “What do you mean it hasn’t even started formal production — what are you actually doing with your time then?” [Okay, it’s time for a full blog on this…]

The past two weeks have been coveted time because my kids have been away visiting their grandparents for the Spring Festival (or Chinese New Year). Most of China is on holiday to celebrate this new dragon year. (P.S. Above is, hands-down, my favourite dragon image of the season!) During this festival season, commerce stops, people rest for an average of 2 weeks, but many schools are out for a whole month. The city is quiet and, like during our Christmas season in the West, most Chinese people take this time to visit with family and reconnect with friends. Some even go on holiday to warmer climates.

In other words, things slow down.

Knowing my kids would be away, I decided to go nowhere … except into the hole of my studio (see pic above) for a two-week, disciplined, musical prep session for the next body of work. According to the calendar and the coming month of March, it’s been nearly 3 years since I released any music and, because I’m writing songs all the time, my computer now possesses an overflowing folder called “Ember New Songs 2020.”

Why 2020? Because, despite the fact that the last album was released in 2021, the songs I wrote in late 2020 simply didn’t make it onto the cutting room floor for that project (“Mid-March Meltdown”). An album is at least six months of work, so by the time they were written, the other songs were already being mixed. That means, I’ve spent as many as 4 years with some of these songs, honing them with the band during live performances. Lots of tweaking, tweaking, and more tweaking.

(Don’t confuse that word with “twerking” — aya!)

When I write a new song at any point, I usually start from voice or guitar and then widen the instrumental arrangements after the song feels solid, structurally. By “structually,” I mean its horizontal arrangement: i.e. Intro-Verse1-Chorus1-Verse2 etc. There are lots of ways to structure a song, but the I-V1-C1-V2-C2-B-C3-C4-O is the most common in popular music. (Those letters stand for Intro, Verse, Chorus, Bridge, Outro, respectively.) It takes awhile before I’m sure that the way I want the song structured works for the overall message.

I don’t always use this typical structure, but my recent music of the past few albums has leaned more towards writing songs that people can sing along to, so I have more and more songs that naturally fall into this pattern. I liken structure to piecing together the bones of the song — the skeleton, if you will. These skeletal parts have harmony as well, in the form of chords. They get fixed into that horizontal structure. Picture any audio software, and the song will start on the left, just like the way we read text, and plays until it finishes on the far right. Once I have this the way I want it, I move onto the instrumental arrangement.

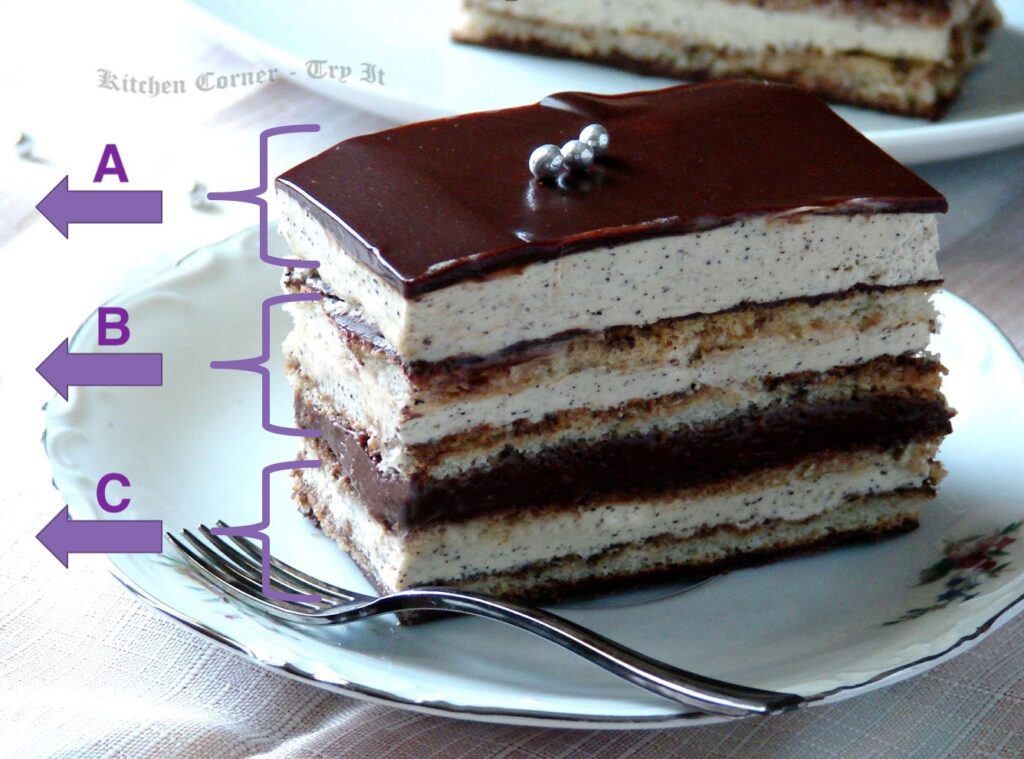

Instrumental arrangement is what I consider the vertical structure of a song. Like a layered cake, songs need their layers to widen out the sonic spectrum of music. (And I suppose, like a skeleton, a song needs some fattening up at this point! Cake is the perfect analogy for that!) So, at the sonic bottom of that cake are the “bed tracks,” or the bass and drums (includes beats and low pads and any textural samples.) (C).

Then, there are the chordal (or harmonic) layers, like keys and guitar (B), which are followed by the melodic layers or single-note instruments like voice, trumpet etc. (A). These aren’t mutually exclusive, of course, because as soon as you add a vocal harmony, you create a chordal layer at the top of that arrangement cake. And if you have a single-note synth keyboard lick, for instance, it might be playing alongside of a single-note electric guitar lick, which also builds a chord. But the point is that the single-note, melodic top layer of the song is really what the average listener notices first. That’s where the hook usually lives, drawing people in. Not unlike those little silver balls on the slick chocolate topping in the picture below that decorate the cake…

So, back to the task: I walked into my studio on the first day of my parenting freedom and I decided that my goal was to have 5 (new) demos fully ready to present to my producer by the end of these 2 weeks. Of the 17 new songs in that folder that I have now amassed since 2020, 7 of them are already flushed out with the band. In other words, the skeleton has long been set in place and the (vertical) instrumental arrangements have also been decided. At least 5 of these will be tracked in a Shanghai studio in the month of March with live players.

So what about these 5 that I wanted to do? They’ve lived for a long time in the “Ember New Songs 2020” folder, but they haven’t been fully arranged. They had skeletons and mostly finished lyrics, but only a few had been built up (with beats and midi bass and loops) to find themselves fully fleshed out with both horizontal and structural muscle. But, even those few had to be tweaked considerably.

On average, once I start to fully “map out” a song, it can take an entire day (roughly 8 hours) of concentrated focus. Not only must I settle on a tempo and record any organic ideas from guitar into my software, but it requires making sure I then have the song in my audio software (Logic) all lined up properly–the chordal sections that repeat (like the choruses) will be cut and pasted properly into their respective zones, and at the end of this day I’ll have an idea of a basic drum feel and I’ll have selected various loops to achieve that. I’ll also have created a basic bass line with a midi keyboard and I’ll know the song’s key and chords intimately, simply because the whole day will be about lining up notes.

The second day is for more sound selections, more instrumental layers, and the constant tweaking to make things sound better. Sometimes I realize that I simply don’t like a lyric and I spend an hour working out that kink in the verbal message of it all. Sometimes I come back to the song on the second day and I realize that the whole “feel” or groove is wrong and I have to adjust the tempo and start again with any instruments that were recorded directly into the song, like guitar. Often (too often), I find out that the ‘bridge’ just doesn’t work (or some other skeletal component is weak) and I have to pretty much break a bone in the song and move large sections of music around to accommodate whatever I take out or put in its place. There’s a lot of destruction and recreation in these hours, sometimes coupled with a lot of profanity muttered under my breath!

When I have the song at a place where I think it finally can stand on its own two feet, that’s when I export it as an MP3 and go for a walk with the dog with the song on a loop in my earbuds. Sometimes I do this process while cooking dinner too, but the point is to listen a bit passively so you can hear what jumps out as “wrong” or “not working” or simply “boring.” After decades of songwriting, I’ve amassed some tricks of the trade, but these are so commonly used that they often result in a musical change that any listener would expect, which will instantly make the song forgettable. The best moments are when I can solve a riddle within the construction of a piece without resorting to a typical solution. When these kinds of decisions sound natural but are actually eccentric or counter-intuitive musical choices, that’s when I know that this song will at least not sound predictable, which may be the key to its longevity in a playlist.

When I’ve taken the time to listen away from the screen — so with no eyes involved, just my ears — then I can do a final layer of tweaking and that’s probably the third day of the process, and it’s around this time that I present the song to Gabriel Beaudoin, my partner and musical comrade in life. His perspective is super valuable to me and he is forever helping to improve my songs with his (extremely rich) musical experience. I often call him “the chord doctor” because he can identify one chord within a section that needs “healing.” When he then comes up with the right one to replace it, it’ll always take the song up a notch, but also sends me back into my studio hole for another day to align all the other instruments to this change. No regrets for that extra time, though. Those little changes can sometimes be exactly what the song was missing.

In early February, I had already completed one song in a choppy sort of way (because I was being interrupted by needing to cook meals for children and helping them with their homework and all those other annoying (!) realities of being a mom…). So, if I include that one completed song, I was able to reach my 5-song goal by allotting an average of 3.5 days to each remaining song on my list. Some songs only took 2.5 days and others took a full 4 days. Nevertheless, I now have 5 new ones to present to Tim Rideout (my producer and great friend in Montreal), plus 3 previously completed demos from last year, of songs yet to reach the band.

This whole project will probably be around 10-12 songs, as the weak ones will be culled, and they will be released as singles to eventually coalesce into an album.

I’m so excited! When the fifth song was exported and in my earbuds, I joined some friends for a meal downtown and a few drinks afterwards. It was a celebratory moment for me, but hard to explain to others exactly what all of these hours have meant to me as a musical creator. People just can’t really wrap their head around what it is a person like me does with her time.

Imagine! Altogether I’ve spent over ONE HUNDRED HOURS of work on only five tracks, and they’re only in the pre-production stage. If we settle on 10 tracks as a calculation number, the pre-production stage will be about 200 hours of work, not counting the original writing stage that these songs all went through. Then, they’ll all go to Tim, they’ll come back to me for final vocals and guitar tracking, they’ll be distributed to some other players for final remote tracking as well, then they’ll go back to Tim for more production, then into mixing, then mastering, then promotion. It’s impossible to gauge exactly how many thousands of hours the final songs will represent as a batch.

What I do know, though, is that when original artists have to arm wrestle a venue into paying them properly for their presentation of this kind of work, it demonstrates such an enormous misunderstanding of what it takes to do what we do. We do it not for the recognition of this time, or even for the “dozens of dollars” we are paid to present it, mind you, but for the joy that music can possibly deliver to others. When there are those (like you) who have made it to the end of this blog post and really respect the time and energy artists give to create their work, that’s when we feel seen and appreciated.

Thank you to those friends who asked those questions and prompted this writing.

Thanks for all your support.

Thank you for caring!

Now I gotta go and export some songs…