Grounded in Toronto: AGAIN

It is not surprising that the Chinese bureaucracy is confusing. Even Chinese people express this, acknowledging that paperwork issues are enough to “grow your head,” (让你头大了) which is the literal translation of an expression used to convey the feeling of your head about to explode.

Two years ago, when my son was a newborn and we were returning to China after his birth, we were surprised at the Toronto airport to be refused boarding passes because my daughter’s temporary entry/exit visa had expired. Knowing the document would expire during the time of my late-stage pregnancy and post-partum period in Canada—a stay of 4 months that eclipsed the 3-month duration of said permit—I had asked in advance, in China, about whether or not we would be allowed to return Beijing anyway. “Shouldn’t be a problem,” I was told. They further explained that initially travelling within the three months would be enough to validate the document.

Well? They were wrong.

You may be reading this wondering why she couldn’t just travel on a passport with a Chinese visa like other foreigners do. The problem is that her Canadian passport is not valid for entry/exit into China. Nor is my son’s. That’s because China deems children like mine as retaining their Chinese nationality despite having had another country’s passport issued. If they were to acknowledge this (foreign) passport, they would contradict their law of officially banning dual citizenship for its people.

Confused yet? You see, in China it is not permitted to have two nationalities, so no one is actually allowed to have two passports. Nevertheless, children with Chinese nationals as parents—even just one—are considered to be Chinese in the eyes of the Chinese government until they are 18 years of age and can decide for themselves as to which country they’d like to officially belong, even if they have a foreign passport.

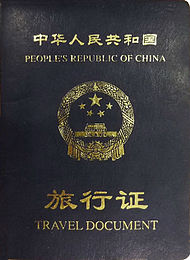

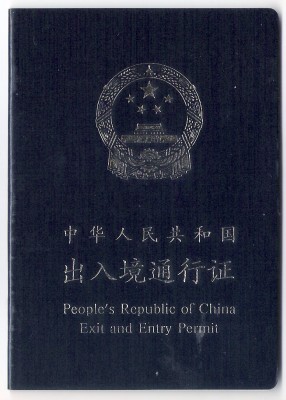

Therefore, they can’t be issued Chinese passports. They need something different. Something special. The first option is an entry-exit permit. It’s the single-use, 3-month document that we had had issued for our daughter when I returned to Canada to birth our son. But, a substitute for this document is simply called a “travel document,” both of which function as a passport in their own right, making their Canadian passports irrelevant.

(Only in China can bureaucracy maneuver a series of policies capable of transforming a passport—a document recognized by every country in the world as official—into an irrelevant booklet unnecessary at the customs desk.)

The one important distinction relevant to these two options is that “travel documents” are only issued outside of the country. They are the equivalent to the single-use 3-month entry-exit permit, but no one tells you about them on the mainland. We only learned about these “travel documents” (issued by Chinese conconsular offices overseas) when we were turned away at the airport back in 2013. And guess what? They’re valid for multiple entries for two years. Yes, you heard me correctly. That beats the 3-month, single-use permit by a long shot.

Well, all of that back-story was meant as an introduction to my latest adventure that has me typing this while stuck in Canada. You see, my son’s documents expired while we were over here—his two-year “travel document’—and I was not permitted to re-apply for a renewed document without the presence of his father. I am here alone, travelling with my two kids, and midway through my trip I went to the consular offices and inquired. Without the second parent, they shooed me away. I would have had to prepare notarized proof of my husband’s identity before returning to Canada in the first place, they told me. They then responded in the affirmative that, yes, I could return back to China with this document at the end of the month. I erroneously assumed I was off the hook.

The problem lay in the lack of specific language. The document expired on of 21st of August. Our flights were booked for the 30th. What they meant, I see now, is that I could use the document until August 21st. But, predictably, at the airport this summer on August 30th 2016, I was once again turned around—grounded in Canada.

But this time: ALONE.

Solo with two children and five large suitcases stacked on top of one another, I tried to quell the panic into a slow boil somewhere under my ribcage. I steeled myself for a series of steps: put the baggage in storage, stand in the ticketing line to re-book my return flights for 48 hours later, take the train back to the city to a friend’s house, organize ourselves to visit the Chinese consulate in the morning during their opening hours: just a small window between 9am-12pm. Pray to the gods of bureaucracy.

The next morning, I fully expected that the consular office would see our plight and issue an extension to the existing document. After all, I was alone. Their father wasn’t with me. Wouldn’t they see that I was between a rock and a hard place? ie. China, the country, and Chinese bureaucracy?

The answer was a firm “NO.” My only option was to get those notarized documents from my husband confirming his citizenship, his relationship to me, his relationship to his son, etc. By mail, they said. Courier. I needed original documents. And to make up for miscommunication the previous month, they agreed that I didn’t have to make an appointment once I’d gathered all the necessary documents together. (The next available appointment was six weeks away!)

The next problem was that I had my son’s birth certificate in Canada with me. I had likewise left my marriage license in China. These two documents were both on the exact wrong side of the world for this process. And before I could send my son’s birth certificate to his dad, I had to have it translated and notarized and then authenticated by my provincial government and then re-authorized by the Chinese consular office, all of which took three days’ time. Then, upon my husband’s receipt of this birth certificate, he had to go and get his identity fully notarized and mail those documents in their original form over to me in Canada.

Stranded in Toronto, I had to rebook flights once again, this time for ten days down the track in hopes that it would all be sorted before then. I returned to the airport to collect my luggage. A friend offered to let me store it in his garage. I held my breath that each of the bureaucratic steps would be smooth. Each day we had a different office to visit and sometimes the individual stages of a task took twenty-four hours to complete. I had to always have both kids in tow, as well (now aged 2 and 4) and was dragging them in and out of boring waiting rooms. I rented car seats so friends could drive us; I took taxis; I re-acquainted with the Toronto subway; and we did a lot of walking. In the case of my husband’s notarization booklet, it took three days before he could go and pick it up completed and then send it off to me. But it was the labour day holiday weekend in Canada. Even courier companies take a holiday. More time would need to pass.

It goes without saying that all this brought my head to near explosion.

Having travel delays due to document issues is a bit like those moments in movies when the main character stops on a street and the rest of the world continues around him. The camera pans in a 360 circle and multiple streams of life continue while the main character is frozen, indefinitely. All the character can do is stare and wait. And, occasionally plead for some corners to be cut.

The Chinese consulate granted me a second concession beyond not having to make an appointment. They agreed to start the process of my son’s “travel document” with just the digital scanned versions of the completed notarized documents that their dad processed in Beijing. I was not, however, going to be permitted to pick up the finished documents until I provided proof of the original notarized documents—the ones expected by courier. So, after I started the process, I sat on pins and needles waiting for that FedEx to arrive containing my marriage license and the notarized proof of my husband’s identity and relationship to our son, not to mention his permission letter allowing me to process the documents without him.

Don’t forget that I’m also the “foreigner,” even though I’m still in my home country. I’m the outsider in this process, despite typing this in Toronto. I need my Chinese national spouse’s permission to get my son back to our home, to reunite him with the rest of the Chinese family. This irritates me, certainly, but it’s taken me a week of complaining and asking finer details to finally understand another layer (beyond just being Chinese bureaucracy that has to be confusing, by definition):

There is too much baby theft. One parent takes a child from one country against the other’s wishes and then there’s a separate category of illegal human trafficking. When Chinese people (who are not yet citizens of Canada) have a child in Canada and the child then becomes a Canadian citizen with a Canadian passport, for instance, if one of the parents decides to leave the country and return to China with the child, they too need this document. If that one parent is permitted to process such a document alone, the other could lose their child to the living maze of one-third of the world’s population in just a simple slap of a consular stamp. There have been too many of these cases in recent years and therefore security has been amplified.

So, I get it. I’m just not happy about it.

When the courier finally arrived today, I nearly kissed the floor of the space I’m staying in, the third of rotating friend’s living rooms whose greatest gift to us this past week has been their sympathies in the form of couch futons. I’m so grateful.

And this is my take away:

Chinese bureaucracy is, indeed, confusing. But, we can’t allow it to let our heads explode. That would be confusing and messy.

+++

Soon, we’ll be home.