Wedding Day Chronicles — Part 3

THE NOODLE CEREMONY

After the dawn portion of our wedding celebration that I wrote about here, we were scuttled up to Guo Jian’s parent’s apartment and whisked into the “marriage bedroom,” or their spare room that was decorated with our photo above the bed, framed, and a new RED bedspread, the marriage colour. I was told to sit at the end of the bed and wait for the auspicious time to eat noodles.

Yes, I said noodles.

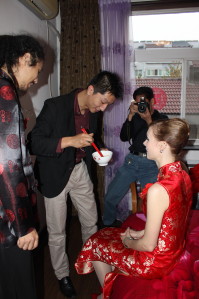

There I was, perched on the edge of the bed in my too-tight Chinese silk dress, and people were crowding in the door frame to take pictures or say hello, some spilling into the room, a photographer wiggled around us to the other side of the bed for better angles, a few people came in and stood by the closet. Guo Jian stood at my knees, occasionally patting my shoulder as though to apologize.

(Well, perceiving it that way made me feel better.)

We were waiting for 6:36am, the auspicious time, so that we could do this noodle ceremony.

Noodle ceremony?

In Chinese culture, noodles are often a symbol of longevity, and in this case, they symbolize a long marriage. But, additionally, there are extended meanings and I had been well prepped. That’s also why I was really over the noodles before they were even served to me. I mean, c’mon! Did I really have to take this seriously when all I wanted to do was just fall backwards and sleep on the bed that I was being forced to sit on?

So, it goes like this:

The day before, a child was sent to Guo Jian’s parents house to sit on our bed and give the bed “baby energy.” Seriously. Guo Jian’s cousin and husband showed up at the door the previous afternoon with their baby in their arms and my mother-in-law made the bed with the new red comforter while they waited. Then the 1-year old infant was then placed in the middle of the bed and photographed until he cried his head off.

His job was to crawl all over the place and “bless our marriage bed with fertility” (because, after all, other people’s babies can be contagious, right?!) and this little guy was not in the mood for crawling. He sat for a few minutes and then just cried until his mother came over to calm him. In any case, the baby was compensated for his job with a yummy apple and the task was completed.

When 6:36am arrived the following morning, Guo Jian’s cousin’s husband (the baby’s dad) came in with a bowl and chopsticks to feed me—the bride—a few strands of half-cooked noodles while cameras flashed until I was seeing spots.

I had been instructed.

I ate the noodles (which were mercifully seasoned with some vinegar and soy sauce) and then they asked me “面条生不生?” (mian tiao sheng bu sheng?), which means “are the noodles raw or not?” But the word “raw” is also the word “birth.” So, if I were asked “生不生” (sheng bu sheng) without the word “noodles 面条 (mian tiao)” in front, the meaning of the question could also be, “Are you going to give birth or not?” And, since it’s clearly all about the woman and her willingness or ability to give birth (?!) (even though science begs to differ!), if I respond “生” then I was confirming that I was willing to have a child with Guo Jian.

And this is exactly what I was expected to say.

I hate scripts. I’d be a terrible actor. I hate being told what to say.

So, instead, I responded with “太多醋吧!” (tai duo cu ba! too much vinegar!), which made everyone extremely uncomfortable for just long enough to satisfy the rebel in me. Then, I made everyone happy by saying “生”(sheng)! I also made Guo Jian say it too. I’d already lectured him several days earlier about the archaic nature of this particular tradition and how he had to agree to have a child too, and that it takes two people to create and raise a child, etc.

Men and their noodles are fairly relevant to the equation, after all.

And he did say it to placate me, but no one really heard him because, in the end, this tradition isn’t about him and birthing is something that only women do, I know. So, technically… yeah, yeah… I get it. Besides, the crowd was too busy cheering the fact that I had said the magic word, thus “prophesizing progeny.” I obviously couldn’t change an entire cultural tradition from one lonely, sleepy, foreign soapbox.

When I was little, around 5 years old at the most, I was at my grandparent’s apartment, in the bathroom, with the door locked, and I was sitting on the toilet by myself with my feet dangling because they couldn’t touch the ground. I was minding my own business in more ways than one.

Suddenly there was a huge commotion at the door. There was banging and yelling and rattling of the doorknob and then more yelling and then “Are you okay, sweetie?” repeatedly asked of me and I just got… more and more scared. I couldn’t say anything. I certainly couldn’t relieve my bowels or bladder. I froze there, perched on the throne, wondering what the hell was going on.

Tongue-tied.

Finally, they took the hinges off the door. And as it was hauled from its closed, protecting position, both grandparents, my uncle, my two cousins, my sister, both my parents and my aunt formed a collage of heads all peering into the bathroom at me with my pants dangling from my ankles. I looked back at them all, terrified and nearly naked.

“You can’t lock this door!” my grandmother told me, crossly. “The lock is broken. You wouldn’t have been able to get out!” I nodded numbly. I still hadn’t moved. Everyone else was suspended in a moment of silence as they all stared at me and I stared back at all of their many sets of eyes.

My grandmother broke the spell with an awkward, apologetic smile as she asked me, with sugary sweetness, “Are you going number 1 or number 2, honey?” I just remember being doubly embarrassed by the question and not whether I answered it or not. Wasn’t it obvious what I was in there for? Did it need to be specified? My modesty folded in on itself leaving only my mortification in its wake. I remember staring down at my underwear resting open on my sneakers wanting to flush myself away.

So, thirty years later, when I was sitting there waiting for the ridiculous half-cooked noodles to be served to me and being stared at by Guo Jian’s extended family whom I barely knew, photographers, my own parents and one of my chosen sisters, Cheryl, and my Beijing friends Valentina and her husband Liyang (who were there standing up for us), while also feeling slightly trapped by my fatigue like I was floating in a drug-like state, this memory suddenly washed over me.

It was the flushing toilet waters of time, catching up to me.

I was five years old again and everyone was staring at me with my pants down.

And then came the embarrassment.

I know this wasn’t our house and it wasn’t really our marriage bed, but that’s what it symbolized. It’s such a private thing. The bedroom should be a couple’s private, sacred space, don’t you think? Yet, with so many people in the bedroom, or staring in from the doorway, I was being asked to publicly announce if my husband and I were going to copulate in order to make a baby!! Why didn’t I just take off my clothes right then and there?

It hadn’t occurred to me that I’d feel so naked in that moment.

But there it was. I was already trapped by the locked door of marriage (that no one was ever going to pry off the hinges for me), and at the mercy of everyone else’s panic and expectations, traditions and practices that had nothing to do with me, my hopes, my ways, my peace of mind.

Or at least, this is what the panic was telling me.

Oh, and the sleeplessness.

And then it was over. The crowds dispersed. We were officially told we could take a nap for two hours before the main event’s banquet would start. Our next act in the “wedding play” would begin at 10am.

We were finally able to close a door and collapse.

Into sleep, not each others’ arms.

Neither of us wanted to do anything more related to noodles!